![]()

Kári Gunnarsson

Professional badminton player from Iceland. Interested in high performance. Studied political science. Excited about technology, innovation and human nature.

https://medium.com/@krigunnarsson

August 8, 2020.

For the past three years the Tokyo Olympics that were supposed to be held this summer had been my big goal. I went from being a full-time student to being a full-time athlete living an ascetic life in a high-performance academy with a regimen of two practices a day and full attention to recovery, nutrition and sleep — all the while competing in 30+ countries, logging miles corresponding to a return trip to the moon. Like a lot of fellow athletes I had planned on retiring after the Olympics.

With the outbreak of the global coronavirus pandemic came what the Icelandic author Andri Magnason has called the Apausalypse, “a sudden, forced pause in habitual ‘doing’. An unavoidable invitation to observe and reflect on our ‘being’”. For athletes working towards big goals, such as the Olympics, the Apausalypse may seem particularly nihilistic. Many have seen their facilities close and all events within the foreseeable future being canceled.

The Apausalypse and the ensuing deepfreeze of normal society provided time for contemplation. In my case, reflecting on these years of high intensity training and competition, I decided to make a conscious effort to articulate the most valuable lessons I want to bring from professional badminton into my next chapter of life. In this article I want to highlight two dimensions of questions I myself have grappled with:

- Practice philosophy: How are you improving from your daily practice?

- Mental game: How do your emotions affect your performance?

As I see it, these are the two main force multipliers in sports. And probably in life, too. Let’s have a look at them one by one.

Practice philosophy: the deliberate approach

What is practice and how do you improve from it? As an athlete that is a question you need to have a clear answer to. So let’s talk about practice (shoutout to Allen Iverson). The Oxford English dictionary defines practice as: repeated exercise in or performance of an activity or skill so as to acquire or maintain proficiency in it. Judging from this definition you might think that the amount of “repetition” is what makes people stand out. However, there are only so many hours in the day and the body also has its limits. There are many things you can do to take care of your body and prepare yourself for practice but the bottom line remains the same: beyond a certain amount of practice you start exposing yourself to injuries. And within every sport hundreds, if not thousands, of athletes around the world will be balancing the fine line of pushing their limits physically. Pushing your physical limits is therefore merely an entry-level requirement if you want to reach the upper echelons in sports. At this level, it is all about the quality of your practice.

My concern with practice philosophy grew out of necessity from having been a free agent for a few years, practicing for extended periods in different countries and being exposed to different ways of doing things. In order to make sure I was improving and not just going through the motions I started thinking more systematically about the above question: what is practice and how do you improve from it?

I settled on the answer that practicing deliberately is the game changer. That means having clear goals and designing your practice systematically with those in mind. In the end, this is what allows you to take qualitative leaps in your game or whatever it is that you’re doing.

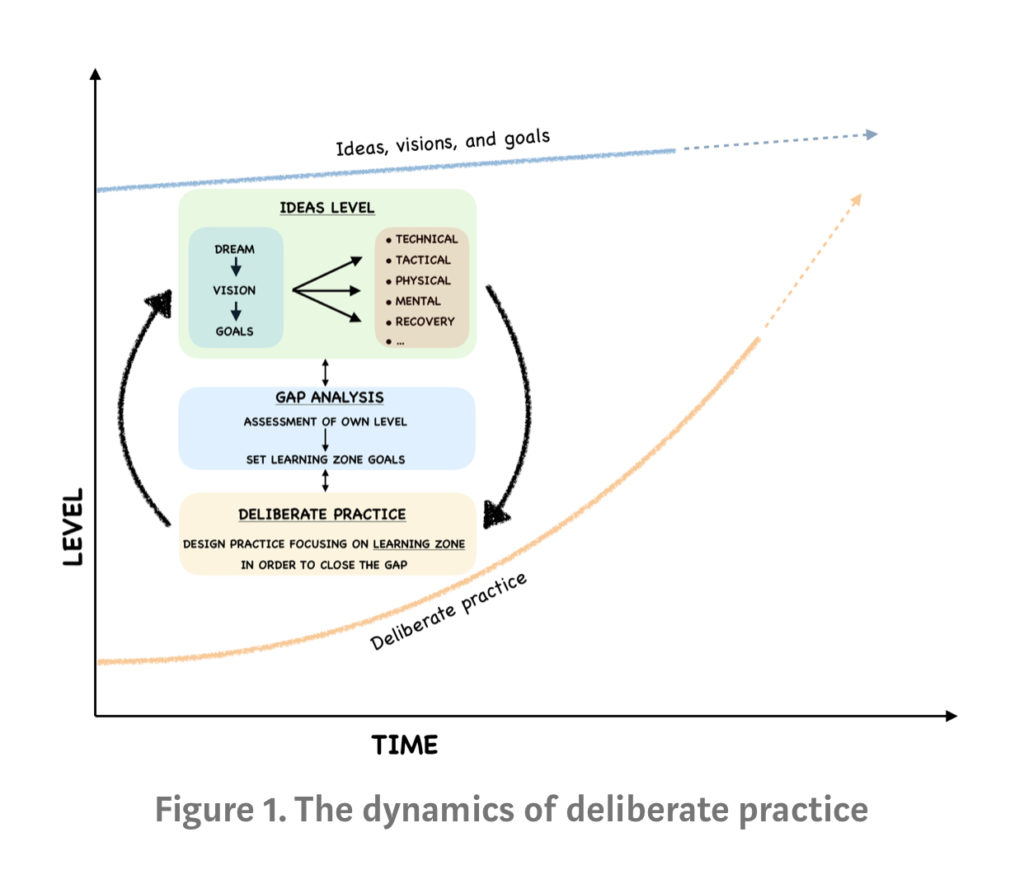

Let’s break down the elements of what a deliberate practice is. There are two levels to deliberate practice: first, it’s vision-driven and goal-oriented; second, it’s tailored and designed to focus on goals that are outside your comfort zone. Importantly, the two levels are constantly revised through an ongoing gap analysis. I’ll discuss the two levels separately below.

THE IDEAS LEVEL: IT STARTS WITH A DREAM

It usually starts with a dream. I remember being glued to the TV for a week during the 2000 Sydney Olympics, being transfixed by the beauty of the sport. It felt like a calling. As a kid I would spend most of my free time playing and having fun with it. I managed to become one of best kids in Europe and at the age of thirteen won what was considered the unofficial European Championships. Around the transition into seniors I was less competitive for a few years while I studied at University and worked on the side. Then 3 years ago I finally made the decision to set all other things aside in order to chase the childhood dream of making it to the biggest stage of them all: the Olympic Games. I had just moved back from San Francisco without having practiced at all for half a year. I realized that I needed to, not just get back in shape, but also raise my level considerably. So I began meticulously studying the best players. I started working with a coach and together we developed a vision for what type of game I wished to play.

Once you have a clear picture of the type of player you want to be, you need to make an assessment of your own strengths and weaknesses. This is the gap analysis which, importantly, is not a one time exercise but a continuous and iterative process. It’s about reflecting, taking notes, and planning. This is how a big goal is broken down into a roadmap of actionable, short term goals. In other words, a path towards your big goal will start to crystallize in your mind.

DESIGNING YOUR DELIBERATE PRACTICE

The gap is the difference between where you are now and where you strive to be. Having built a clear vision in the ideas level of where you want to end up, you can lay out a practical roadmap of smaller, short-term goals that will take you there through deliberate practice. These short-term goals are actionable and cover specific aspects and categories of the game. Within every category you’ll have the option of working within a spectrum of specificity. Examples of short-term goals with different degrees of specificity could be:

Technical: “steepen the angle of sliced drop shots from back court” (specific) and “be mindful of body posture when attacking from the back court” (more general)

Physical: “work on hip flexibility in order to stay explosive in defensive positions with low center of gravity” (specific) and “build muscle mass in legs with explosiveness in mind” (more general)

Tactical: “When attacking on front court vary shot selection based on an awareness of the opponent’s body position” (specific) and “cultivate tactical patience to play long and physical games when required” (more general).

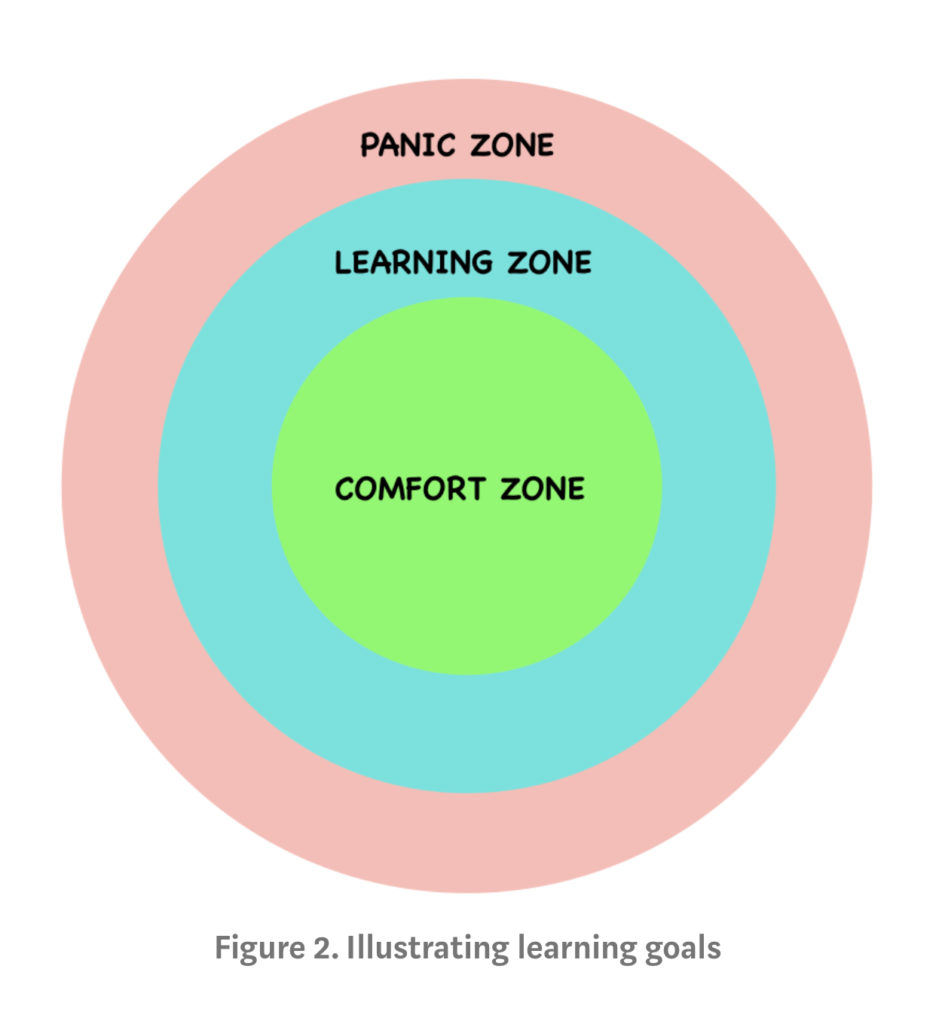

In figure 1 the improvement space is defined as the area between the two graphs. You want to close the gap step by step with short-term goals that are outside your comfort zone. This may seem obvious but my experience is that most people instinctively prefer to do stuff they are already good at. There’s a reason it’s called the comfort zone. The problem is that you won’t get much better staying there. Doing stuff that you are not particularly good at doesn’t always look pretty and it might be a bit uncomfortable in the beginning. But true discipline requires that you work within the learning zone, as seen in figure 2. Gradually the comfort zone expands — what was in the learning zone before moves into the comfort zone — and the gap becomes smaller and smaller.

I remember the great Kobe Bryant once saying that he would purposefully seek to match up with opponents that were stronger than himself at specific things that he was working to improve — he of course had the confidence that with his ruthless determination to improve they wouldn’t be stronger than him for very long.

Once Nathan Milstein, who is considered one of the finest violinists of the 20th century, asked his teacher if he was practicing enough. His teacher replied: “ Practice with your fingers and you need all day. Practice with your mind and you will do as much in one and a half hours.” There’s a big difference between just going through the motion of something versus being intensely focused on what you are trying to achieve with a given practice. With deliberate practice you are quite literally pushing your limits. This comes with mental strain and therefore the other dimension I want to highlight in this article is the mental game.

Mental game: Know thyself

Anyone who has been competitive in sports will know that mental strength is important. We are not machines but human beings with emotions that have the power to be anything from self-defeating to a lever to greatness. Deliberate practice is in itself a highly mentally demanding endeavor. In order to persistently work outside your comfort zone you will have to keep your pride, vanity and perfectionism in check. Ultimately, professional sports is about winning. The ability to stay calm and collected in match situations is often seen to be the decisive factor in determining who wins, and it’s an art mastered through self-awareness and command of one’s emotional dispositions. This self-discovery process starts with asking the question: “under what (emotional) conditions do I perform best?” And vice versa.

I’d like to highlight a couple of tools that have helped me sharpen my mental game both in practice and in competition: first, the idea of the inner game; second, building trust in the process (as opposed to outcome obsession).

THE INNER GAME

In sports there is an Outer Game which are the tangible things about our sport, the court, the equipment we use, the rules of the game. Then there’s an Inner Game which are the obstacles that our mind sometimes sets between us and our external goals. These obstacles go by many names — such as Pride, Vanity, Anger, Expectations, Worry, Fear, Perfectionism — and they lower the quality of practices and make us lose games. I am of course speaking from personal experience here, and that’s why I decided to take the Inner Game seriously.

I brought a great deal of perfectionism into competitive badminton from an early age. When I was 13 I didn’t eat any candy for a year because I thought that might give me an edge. I had very high standards for myself and an expectation that I should always be one of the best. Naturally, that made me a sore loser and also instilled in me a — at times debilitating — tension and obsession with results. “ I… Cannot… Lose… This… Match”.

The idea of the Inner Game comes from Timothy Gallwey’s 1974 book The Inner Game of Tennis. The book describes the idea of how our “self” can be split in two. Self 1 is the conscious self and Self 2 is the unconscious self. Self 2 is the doer, executing movements that we have taught our sensorimotor system, while Self 1 is the thinker, often predisposed to passing judgement. This framework allows us to gain a better understanding of how our thinking and emotions affect our natural flow and performance. Imagine you make a backhand shot that goes into the net and you get upset thinking to yourself “what a horrible shot, I just can’t manage to hit a proper backhand”. Now, a shot that goes into the net should be considered a neutral data point, however, Self 1 reacts by passing a negative judgement on Self 2’s general technical ability to hit a backhand. When Self 1 is negative it is natural for Self 2 to tense up. The smooth, quick and accurate movements required in sports come from a state of relaxed concentration, not tightness. Tightness, in other words, is counterproductive to the goal of letting Self 2 do its job as tightness-inducing criticism easily turns into a vicious cycle of declining performance.

What this framework then teaches us is to pay attention to how we “talk to ourselves” and to, if not completely let go of, then at least be better at quieting our self-defeating self-judgement. If we learn to be more observant and detached from value judgements we are better able to see things for what they are and to make progress based on unbiased assessments of our level. For someone prone to ruthless perfectionism and self-flagellation, like myself, this framework has helped me move toward a more stoic calm (actual Stoicism is great for that, too).

TRUST THE PROCESS

There’s a quote often attributed to the Navy Seals: “ Under pressure, we don’t rise to the level of our expectations, we fall to the level of our practice”. The quote expresses process-orientation par excellence and should be the mantra of your deliberate practice. Often in popular culture there’s an expectation that the athlete, or the hero, will rise to the occasion and produce something extraordinary in the moment of heat. That’s not how it works in reality. In reality, the better prepared athlete will, on average, win. And that’s the thing, the trust in process is a trust in a probabilistic approach. It’s a trust that through your deliberate practice you steadily improve your capabilities so that in any given performance situation you improve the likelihood that you will succeed, by making better decisions and executing more precisely.

In other words, trusting the process is an acquired mindset aimed at doing away with an obsessive outcome orientation. The thing is that outcome is never completely within the limits of control. Measuring your success exclusively in terms of outcome is a sure-fire way to add self-defeating pressure to yourself. Rarely does it help to obsessively focus on “not making mistakes” or “the tragedy it would be to lose this match”. Whether you win a certain point or even any given match shouldn’t be “do or die”. Process orientation reminds us that, in fact, it’s statistics based on how well you have prepared — and the good thing is that you can increase your odds.

The process, like deliberate practice, implies a long-term view. Even though the process is guided by a big goal, as described earlier, it is ultimately about putting the emphasis on the daily work it requires to reach that goal. It’s about trusting that your plan and your dedication to execute your plan will bear fruit in the long term. It’s about accepting imperfection, battle scars and losses along the way. We focus less on outcome in order to better our chances at success.

Mostly, though, it’s about freeing yourself from the self-flagellating whip and finding joy in what you are doing. Life shouldn’t be a checklist of goals that you have reached. The old cliché about enjoying the journey definitely rings true here.

Mark your destination and enjoy the ride

So what are the life lessons here? Sports are like a highly compact version of real life: there are dreams, challenges and skills that need to be honed. If you are ambitious and you have something you’d like to achieve in life, the concept of deliberate practice teaches us that the most important thing is to visualize where you want to be and make an assessment of the gap you need to fill in order to get there. This provides us with actionable steps towards our goals. Ultimately, the mind is both the compass and the engine when working towards big goals. Cultivation of self-awareness through Inner Game and Process orientation helps us become better performers by freeing us from self-defeating judgment, enabling us to focus on the process that will take us towards our goal.

Baseball legend Yogi Berra once quipped “If you don’t know where you’re going, you might wind up someplace else”. We could add that if you don’t have a reasonable assessment of where you are and what challenges you might have to deal with, it’s hard to lay out a roadmap to where you want to go.

Find me on twitter @karigun ?

BadmintonBladet flest nyheder om badminton

BadmintonBladet flest nyheder om badminton